Rebranding is always a tricky exercise, but for one field of technology 2013 will be the year when its proponents need to bite the bullet and do it. That field is alternative energy. The word “alternative”, with its connotations of hand-wringing greenery and a need for taxpayer subsidy, has to go. And in 2013 it will. “Renewable” power will start to be seen as normal.

Wind farms already provide 2% of the world’s electricity, and their capacity is doubling every three years. If that growth rate is maintained, wind power will overtake nuclear’s contribution to the world’s energy accounts in about a decade. Though it still has its opponents, wind is thus already a grown-up technology. But it is in the field of solar energy, currently only a quarter of a percent of the planet’s electricity supply, but which grew 86% last year, that the biggest shift of attitude will be seen, for sunlight has the potential to disrupt the electricity market completely.

The underlying cause of this disruption is a phenomenon that solar’s supporters call Swanson’s law, in imitation of Moore’s law of transistor cost. Moore’s law suggests that the size of transistors (and also their cost) halves every 18 months or so. Swanson’s law, named after Richard Swanson, the founder of SunPower, a big American solar-cell manufacturer, suggests that the cost of the photovoltaic cells needed to generate solar power falls by 20% with each doubling of global manufacturing capacity. The upshot (see chart) is that the modules used to make solar-power plants now cost less than a dollar per watt of capacity. Power-station construction costs can add $4 to that, but these, too, are falling as builders work out how to do the job better. And running a solar power station is cheap because the fuel is free.

Coal-fired plants, for comparison, cost about $3 a watt to build in the United States, and natural-gas plants cost $1. But that is before the fuel to run them is bought. In sunny regions such as California, then, photovoltaic power could already compete without subsidy with the more expensive parts of the traditional power market, such as the natural-gas-fired “peaker” plants kept on stand-by to meet surges in demand. Moreover, technological developments that have been proved in the laboratory but have not yet moved into the factory mean Swanson’s law still has many years to run.

Running a solar power station is cheap because the fuel is free

Comparing the cost of wind and solar power with that of coal- and gas-fired electricity generation is more than just a matter of comparing the costs of the plant and the fuel, of course. Reliability of supply is a crucial factor, for the sun does not always shine and the wind does not always blow. But the problem of reliability is the subject of intensive research. Many organisations, both academic and commercial, are working on ways to store electricity when it is in surplus, so that it can be used when it is scarce.

Progress is particularly likely during 2013 in the field of flow batteries. These devices, hybrids between traditional batteries and fuel cells, use liquid electrolytes, often made from cheap materials such as iron, to squirrel away huge amounts of energy in chemical form. “Grid-scale” storage of this or some other sort is the second way, after Swanson’s law, that the economics of renewable energy will be transformed.

One consequence of all this progress is that subsidies for wind and solar power have fallen over recent years. In 2013, they will fall further. Though subsidies will not disappear entirely, the so-called alternatives will be seen to stand on their own feet in a way that was not true in the past. That will give them political clout and lead to questions about the subventions which more traditional forms of power generation enjoy (coal production, for example, is heavily subsidised in parts of Europe).

Enlarge

Fossil-fuel-powered electricity will not be pushed aside quickly. Fracking, a technological breakthrough which enables natural gas to be extracted cheaply from shale, means that gas-fired power stations, which already produce a fifth of the world’s electricity, will keep the pressure on wind and solar to get better still. But even if natural gas were free, no Swanson’s law-like process applies to the plant required to turn it into electricity. Nuclear power is not a realistic alternative. It is too unpopular and the capital costs are huge. And coal’s days seem numbered. In America, the share of electricity generated from coal has fallen from almost 80% in the mid-1980s to less than a third in April 2012, and coal-fired power stations are closing in droves.

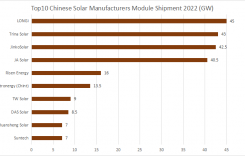

It may take longer to make the change in China and India, where demand for power is growing almost insatiably, and where the grids to take that power from windy and sunny places to the cities are less developed than in rich countries. In the end, though, they too will change as the alternatives become normal, and what was once normal becomes quaintly old-fashioned.

Geoffrey Carr: science editor, The Economist